Table of Links

II. Expectations of Blockchain Accessibility

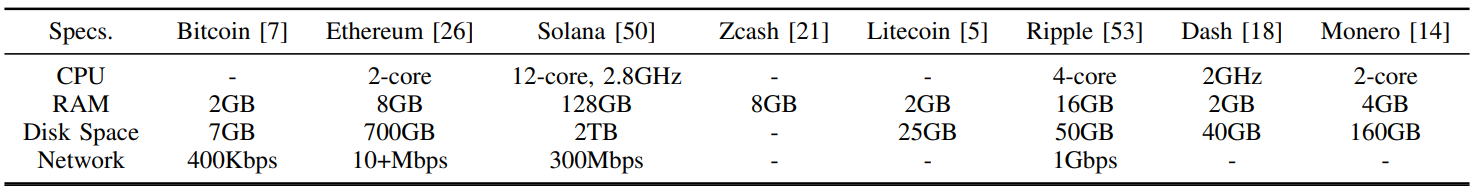

III. Approach I: Maintain a Ledger Locally - Run a Full Node

IV. Approach II: Query a Third-Party Ledger-Node-As-A-Service (NAAS)

V. Approach III: Light Node - External Query & Local Verification

VI. Concluding Remark and References

IV. APPROACH II: QUERY A THIRD-PARTY LEDGER - NODE-AS-A-SERVICE (NAAS)

If a user cannot afford to run a full node themselves, they must outsource the synchronization of blockchains to some third party. While typical users may be tempted to entrust their crypto coins and assets to an all-in-one cryptocurrency exchange, such as Crypto.com [16] and Binance [6], for exchange of easy accessibility, we consider the approach fundamentally flawed. Because the user has no access to the asset without the consent of the exchange, they cannot claim that they effectively own the asset: the recent collapse of FTX [31] reveals the risk of the exchange being insolvent and the user’s asset being lost.

![TABLE IIPOPULAR NODE-AS-A-SERVICE PROVIDERS, AS ADVERTISED BY ETHEREUM FOUNDATION [25]. PROTOCOLS SUPPORTED - NUMBER OF PROTOCOLS SUPPORTED BY THE SERVICE. FREE TIER - IF A FREE TIER IS AVAILABLE. MINIMUM PAYMENT - THE MINIMUM AMOUNT OF PAYMENT BEYOND THE FREE TIER (IF EXISTS), PER MONTH. CUSTOM API - IF A BLOCKCHAIN API DEVELOPED BY AND EXCLUSIVE TO THE SERVICE PROVIDER EXISTS.](https://cdn.hackernoon.com/images/fWZa4tUiBGemnqQfBGgCPf9594N2-hd933zz.png)

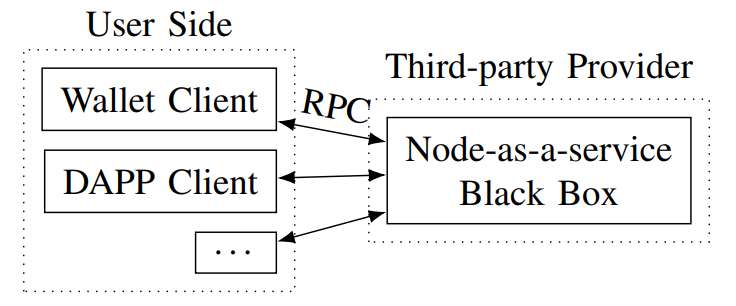

Therefore, if the user wants to keep his private key and still maintain reasonable access to the blockchain, one approach is to purchase a third-party service that answers RPC queries, colloquially known as Node-as-a-service (NAAS) or an RPC node. The clients can interact with the third-party service just as they would with a full node (see Fig. 3).

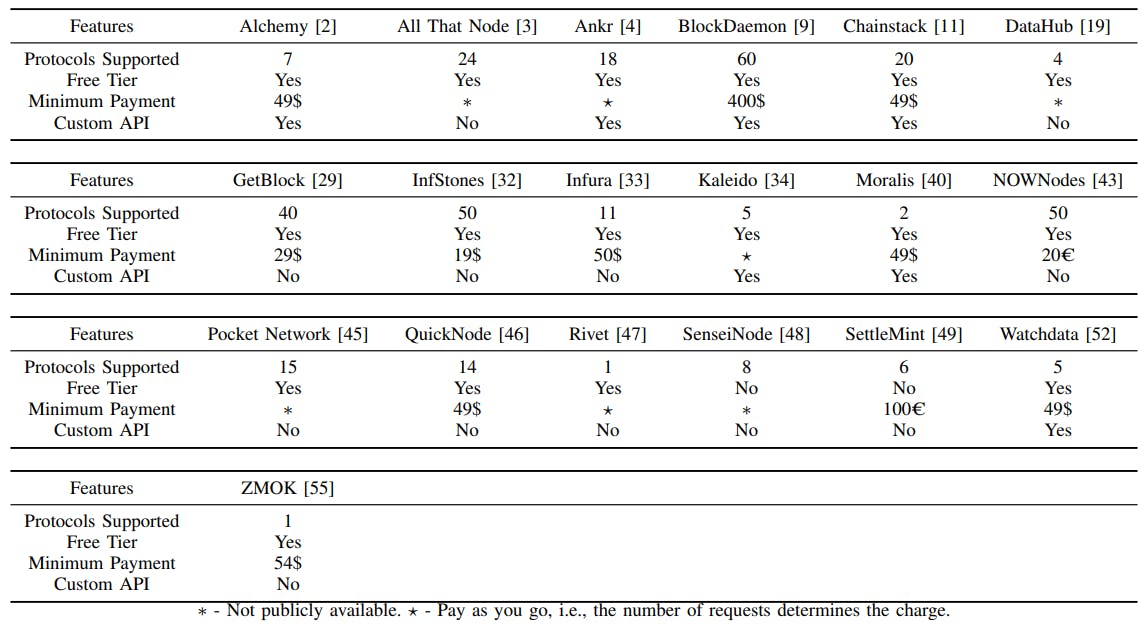

Many active NAAS providers exist in the field, including Alchemy, Ankr, BlockDaemon, etc. Table II provides a list of providers, as advertised by the Ethereum Foundation [25]. While we recognize that different providers offer services with different features and have different pricing plans, which makes an accurate comparison challenging, we pick four uniform measurements to understand the provider: the number of protocols supported, whether there is a free tier, the minimum amount the user needs to pay for a paid tier (per month), and whether or not the provider developed an exclusive API (such as one that handles the NFT) for the service in addition to traditional RPC calls.

A. Pros and Cons

The main benefit of using a NAAS service is that it is more affordable than running one’s own full node because the service provider can build an infrastructure that handles a high workload efficiently. Many providers also have a free tier that allows a limited number of queries.

It is also noteworthy that most providers allow users to access more than one blockchain, which would traditionally require running one full node for each blockchain. Some providers offer exclusive pre-made APIs to handle common use cases, such as NFT. While using such API may reduce the program’s portability, it increases the development efficiency.

The drawback of the approach is also significant: the security assumption of the model now depends on the service provider as a trusted party. Consider the case of Bitcoin’s RPC call getbalance. The client has no way to verify the numerical result because RPC is not designed to ensure data integrity: every user is expected to run a node themselves. There is also no privacy guarantee when the service provider is untrusted: the service provider can see all parameters of an RPC call, thus increasing the risk associated, such as frontrunning [17].

Besides, any attack and incident of the service provider can impact users’ access to blockchain information, thus affecting availability. Ankr was hit by a DNS attack in July 2022, which disrupted its users’ access to two blockchains and placed their funds at risk [36]. Similarly, Infura was forced to censor Venezuelan users due to a US sanction in March 2022 [39]. These cases illustrate that a centralized service provider can become a single point of failure, and additional considerations are needed to ensure the accessibility of blockchains.

B. Open Questions

Node-as-a-service providers form a competitive market: there are 19 providers advertised on the Ethereum Foundation website. However, there is little study on the market: who are the main users? Which service has a better cost-performance ratio for a specific type of user? How profitable can the providers be? An empirical study on this growing market is a challenging topic.

The design of the RPC protocol in this scenario can be particularly challenging since the current RPC protocol assumes the complete trust of the server. However, with the recent advancement of verification methods, such as Flyclient [10], a verifiable RPC protocol may be possible from a minimal-sized root of trust, solving the issue of integrity in the face of an untrusted service provider.

We also observe that it is standard industry practice to employ several services so that at least one is available at any time. Since many providers exist in the field, a unified structure that features a collaboration between providers may provide an improved availability guarantee and some degree of privacy and anonymity to users. For instance, Lava [13] is an ongoing proposal to design a decentralized RPC network blockchain that allows a group of NAAS providers to join together to provide services to users. The users will be charged in LAVA, a new type of coin specific to the network. Both NAAS providers and blockchain validators will stake LAVA to use the system. Unfortunately, Lava’s whitepaper lacks a formal description of security, instead claiming that slashing the funds from bad actors can stop them from providing compromised information.

Authors:

(1) Zhongtang Luo, Purdue University ([email protected]);

(2) Rohan Murukutla, Supra ([email protected]);

(3) Aniket Kate, Purdue University / Supra ([email protected]).

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED license.